Türkiye’s over-zealousness in adding a military dimension to relations in Africa may offer an irresistible temptation to compete with former colonialists like France, but it also poisons Türkiye’s relations with the continent.

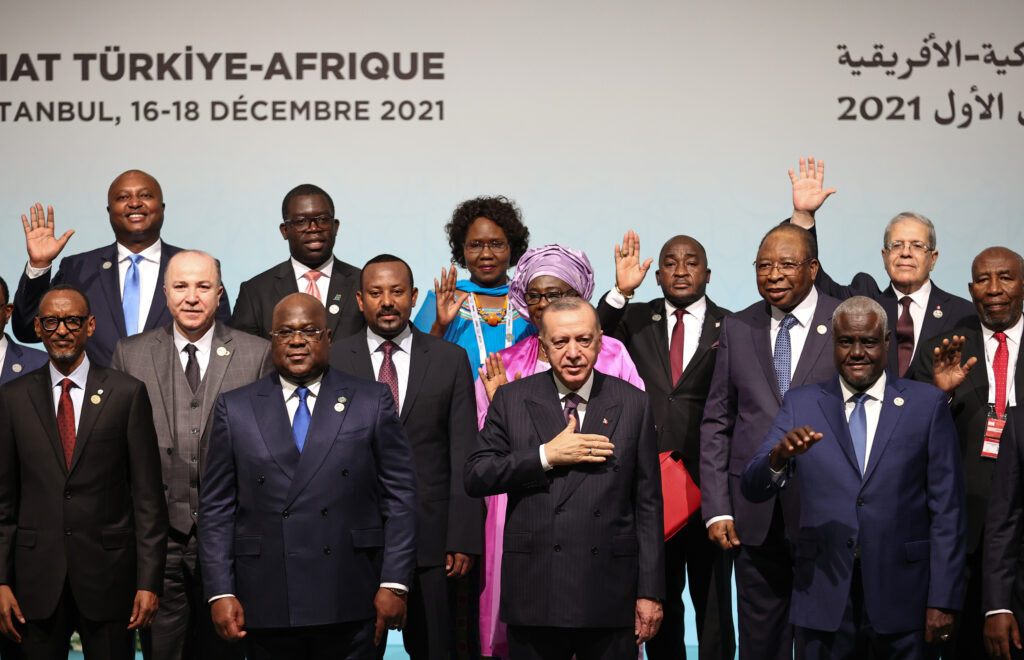

Türkiye is not the only country with ambitious plans for Africa, but its initiatives create more controversy than their real weight due to the noisy rhetoric of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. While Erdoğan’s focus on former French colonies such as Mali, Senegal, Niger, Mauritania, Chad and Gabon intensifies the rivalry with Paris, at the same time Libya and Somalia stand out as places where Türkiye’s ambitions to become a “hard power” are taking hold.

One of the symptoms of becoming an imperial power in recent years can be seen in Erdoğan: Similar to his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin, Erdoğan looks at coups and regime change in Africa with the expectation that the post-colonial power structure will be dissolved then political, economic and even military spaces will open up for them in a new hegemonic order.

While feelings in once-Ottoman-dominated North Africa and the Red Sea coast range from suspicion to nostalgic interest, there is also great potential for cooperation with “untested powers” in many parts of Africa. As regimes that maintain dirty partnerships with former colonialists are overthrown, new rulers looking at the opportunities and cooperation offered by different actors are undoubtedly interested in countries like Russia, China and Türkiye . Erdoğan’s political style of airing the dirty laundry of former colonial powers, especially France, contains the proposition: “We are different, we are not colonialists”.

While being a “soft power” was idealized during the first years of the AKP government, Africa was being increasingly penetrated through the opening of humanitarian aid channels via a mobilization involving public institutions such as the Turkish Red Crescent, Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA), Religious Affairs and civil organizations such as IHH, Yeryüzü Doktorları, Deniz Feneri and Sadaka Taşı. Humanitarian activities such as opening educational institutions, providing health services and drilling water wells have become widespread. Although Türkiye’s “Action Plan for Opening to Africa” dates back to 1998, relations gained momentum during the AKP era with the “New Ottoman” metaphor.

From the very beginning, Erdoğan, has seen Africa as a valuable “virgin geography”. In 20 years since 2002, the number of Turkish embassies in Africa has increased from 12 to 44, the number of business councils from six to 46, and the number of destinations flown by Turkish Airlines (THY) from four to 62. The number of African students studying in Türkiye with scholarships exceeds 17 thousand. Also, thousands of students received education in Türkiye with own financial resources . Both these students and those who learn Turkish in schools in Africa are naturally perceived as Türkiye’s agents of influence. While the network of economic and political relations has expanded in parallel with humanitarian diplomacy, Erdoğan has neither hesitated to drag Türkiye into the field of “fierce competition” after making some room for his feet. While his son-in-law’s company, Baykar, made breakthroughs in the production of unmanned aerial vehicles (drones) with state support, Erdoğan worked as a marketing executive for the products of the Turkish defense industry, especially the TB2 drones, in all the countries he visited. In addition to the drones, Erdoğan’s marketing list includes products such as ships, helicopters, tanks, armored vehicles and howitzer cannons. Consequently, the opening to Africa, which started with the declaration of 2005 as the “Year of Africa” and whose humanitarian dimension was emphasized, has since gained a military dimension.

WHY IS SOMALIA SO IMPORTANT?

Somalia, today home to Türkiye ’s only military base in Africa, is one of the most important pillars of Ankara’s strategy to gain a foothold on the continent. It was a risky but uncompetitive country that many actors avoided as a “troublemaker”. On August 19, 2011, Erdoğan got hold of a wrench which opened the doors for his long-term influence on the continent, venturing to Somalia with marvelous timing during that country’s famine.

Erdoğan has begun to write his play by investing in the lack of central power in Somalia, which is seen as a “failed state” in the hands of pirates in the Horn of Africa, the Islamist Al-Shabaab and unstable governments. The first military relations with Somalia were shaped by agreements signed in 2010 and 2012. While TURKSOM, the Turkish military base established in Mogadishu in 2017 for $50 million, became the cornerstone of Erdoğan’s new Ottoman dreams, the era of “Turkish-trained soldiers and police” began in the Somali security umbrella.

It’s at TURKSOM’s Anadolu Barrack’s where the Somalia Turkish Task Force Command (STTFC) started to train Gorgor (Eagle) Battalions of the Somali National Army. Alongside this military training, he STTFC’s officers and sergeants to be get an accelerated Turkish education. According to Turkish Defense Minister Yaşar Güler, “Gorgor Battalions full of patriotism have become an important role model in African geography.”In addition Türkiye gives consultation to Somalia’s Ministry of Defense, the General Staff and the Land, Naval and Air Force Commands, and provides specialized training for soldiers destined for the Navy and Air Force, as well as commandos and Somalia’s Special Police Forces (Haramcad or Cheetah).

Commandos and police are trained in Türkiye itself, in the commando center in Isparta Türkiye , and for the police in Foça. The result is that the Somali military now has an elite, Turkish-speaking force. A staggering one-third of the Somali Army has been trained in Türkiye with 16,000 soldiers.

But the story does not end here. The two countries took their relations to a new level with “The Framework Agreement on Defense and Economic Cooperation” signed on February 8, 2024. According to Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mahmud, the agreement covers cooperation in Somalia on issues such as combating terrorism, external threats, piracy and illegal fishing, coastal protection and development of marine resources.

In this framework, Türkiye will protect Somali territorial waters for 10 years and contribute to developing marine resources. This is a mission far beyond Türkiye’s reach, not only because Somalia has a very long coastline but also because it has to deal with potential confrontations or challenges with Somaliland and Puntland, de facto independent regions that reject Mogadishu’s authority, along with Al-Shabaab and pirates in the territorial waters.

Al-Shabaab also described the deal, which it called illegal, as a new reflection of Türkiye’s hegemonic ambitions in the region. There is no doubt that the reward for the risks taken here is Somalia’s offshore oil and gas reserves, and in this field there are other actors who have a faster hand than Türkiye . Within the framework of hydrocarbon exploration operations, Houston-based firm, Coastline Exploration, acquired seven offshore blocks from Somalia’s federal government in 2022 paying $7 million to Mogadishu. Chevron, Eni, ExxonMobil and Shell had begun exploring in Somalia in the 1950s but bolted when the civil war erupted in 1991. Meanwhile, ExxonMobil and Shell are reportedly considering a return to Somalia.

In a meeting with Turkish officials in Ankara in early February this year, Defense Minister Abdulkadir Mohamed Nur, who signed the agreement on behalf of Somalia, added a bit of nostalgia to the partnership by stating that Türkiye -Somalia relations date back to the 16th century. “We were proud to have the Ottoman Navy on our side against the Portuguese ships,” Nur reportedly said, referring to the fact that Ottoman intervention in the Horn of Africa played a key role in pushing back Portugal’s colonial ambitions in the region.

Nur’s love for Türkiye stems from his graduation from Ankara University’s Faculty of Political Sciences. Just before Türkiye’s presidential elections in 2023, Nur wrote an opinion piece for the Anadolu Agency in which he explained why it was important for Erdoğan to stay in power. “The people of Somalia, who have intertwined their destiny with that of Türkiye ’s destiny, are eagerly awaiting the results of the upcoming election in Türkiye ,” he wrote, expressing gratitude to Türkiye under Erdoğan’s leadership for its “unconditional support” to Somalia. “Before Erdoğan’s visit, Somalia was a desolate land,” Nur said, describing Türkiye as “an irreplaceable partner for Somalia”. Nur explained that Türkiye had helped Somalia get back on its feet by building hospitals, airports, parliament and senate buildings, roads and agricultural education institutions, claiming that Türkiye had given a spirit woven with patriotism to Somali commandos trained and equipped by Türkiye and that they had dealt heavy blows to Al-Shabaab. Nur also had a message: “It is not only for Somalia, the continued support of Türkiye is required for all oppressed geographies in the world.” This rhetoric was copied from the AKP’s fallacious neo-Ottomanist mentors and shows that AKP cadres have achieved the desired results in Somalia. By the way, the Ottoman geography did not cover the whole of Somalia, but the territory of today’s Somaliland which was named “Zeyla”.

OVERLOOKED RISKS: TÜRKIYE BECOMES A PARTY TO THEIR PARTNERS’ CONFLICTS

The military dimension of relations with Türkiye’s new partners inevitably brings with it certain risks, drawing Ankara into the internal conflicts of these countries. Again, Somalia has epitomized this.

Ankara’s position of strengthening the hand of then-President Mohamed Abdullah Farmajo during a turbulent election process in 2020-2021 sparked substantial controversy. Opposition candidates accused the Turkish ambassador of siding with Farmajo when he accepted the controversial electoral commission in 2020 and they wrote a letter of warning over concerns that Harmacad and Turkish military equipment would be used to hijack the elections. The opposition also asked Türkiye to postpone its arms shipments to Harmacad until after the elections. Türkiye sent 1000 G3 rifles and 90,000 ammunition to Harmacad on 26 December 2020, which were stored at TURKSOM.

When Farmajo attempted to extend his presidential term for another two years during a dispute over how to organize the elections, the opposition took to the streets on February 19, 2021. Harmacad, Gorgor and armored vehicles donated by Türkiye were used to suppress the demonstrations. Two months later, the radio station Mustaqbal was raided by the same forces. The transformation of Harmacad and Gorgor, which were trained against Al-Shabaab, into a tool of political pressure brought Türkiye’s role into the spotlight. However, the Turkish authorities rejected responsibility, stating that Somalia’s federal government was in command.

In order to facilitate military agreements and arms sales, Türkiye does not seek special conditions on where and how they will be used. In other words, it is trying to reach the neo-imperial position more quickly.

This pragmatic approach ensures that the interest-driven status quo remains unaffected by changes in power. Maintaining the status quo is not only about Türkiye’s military base but also about sustaining the interests of AKP businessmen. In Erdoğan’s world of relations, heroism also makes money! Companies such as Albayrak, which operates the port in Mogadishu, and Kozuva (Favori LLC), which operates Mogadishu Aden Abdulle Airport, are part of Erdoğan’s inner circle. In Somalia, shady contracts, irregularities, unrecorded profit transfers, fraudulent accounts, labor murders and bribery scandals involving Turkish companies have come to the fore. But their impunity has not been affected by the change of power in Somalia, the support of a power like Türkiye is not an option that anyone in Mogadishu can ignore. Consequently, Sheikh Mahmud, who replaced Farmajo, became the most ardent advocate of partnership with Türkiye .

US TROJAN HORSE?

There is a parallel between Türkiye’s moves and the US’ efforts to return to Somalia after it left the country in disgrace in 1993 with the Black Hawk Down scandal. While Türkiye spent $1 billion for Somalia in the 10-year period since 2011, the US allocated $2.4 billion for the reconstruction of the country between 2010 and 2020. Since 2014, the US has trained about 3,000 members of the Danab Brigade, a special counter-terrorism unit of the national army. American forces withdrawn under President Donald Trump returned under Joe Biden and after 30 years, in October 2019, the Americans were able to open the doors of their embassy in Mogadishu. Then on February 5, 2024, the US signed a memorandum of understanding with the Somali government to build five military bases for the Danab Brigade.

Nevertheless, it is difficult for the US to catch up with the picture of cultural interaction that Türkiye proudly presents and for the US, Türkiye’s initiatives resemble a pioneering mission. It would not be out of place to suspect that this is in fact a Trojan Horse mission of the US, because there is a geostrategic interpretation that views the Turkish presence as a counter to American adversaries. The escalating competition in Africa has the potential for axis wars. Participating in the Antalya Diplomacy Forum on March 2, 2024, US Ambassador to Ankara, Jeff Flake, said: “We appreciate what Türkiye is doing in Africa, especially in competing with China.

DREAMS DASHED INTO THE RED SEA

Erdoğan attempted a similar move in the Red Sea with a more nostalgic flavor. In December 2017, he persuaded then-Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir to allocate Suakin Island to Türkiye for 99 years. According to the signed agreement, a port was to be built on the island as well as reviving Ottoman artefacts. However, in order not to frighten the squirrels, they refrained from officially announcing the military base. Erdoğan, who had already angered the Gulf bloc led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) with a base in Qatar, made the countries along the Red Sea, especially the Saudis and Egyptians, fear that “the Ottomans are returning to the Red Sea” with the Suakin plans. However, the future of the Suakin deal became uncertain after Al-Bashir’s ouster and the Saudi-Emirati duo opened the purse strings and forced Khartoum to change its axis.

However, the ill-fated Suakin plan unnecessarily raised dust. Egypt was worried that Sudan would expand its claim to the disputed Halaib Triangle in the Red Sea with the power it received from Türkiye . Türkiye’s plans to acquire naval and air bases in Libya were already making Egypt’s nerves jump. To maintain the balance of power, Egypt built the Mohammed Najib Base on the Libyan border and strengthened its military presence in the Halaib Triangle. Meanwhile, while the partnership between Eritrea and Egypt against Ethiopia was developing, Cairo put Bernice, the largest air, sea and land base in the Red Sea basin, into service in 2020. Saudi Arabia and the UAE who were then engaged in a proxy war with Türkiye , were also behind the show of strength from Egypt. There is already an Emirati base in Eritrea and while Türkiye was concentrating on Somalia, the UAE was investing in ports in Somaliland and Puntland, which have unilaterally declared their independence from Somalia.

Meanwhile, Erdoğan showed his pragmatism by hosting in Ankara the two rival actors of Sudan’s post-Bashir era, General Abdulfettah al-Burhan, head of the Sudanese Sovereignty Council, and his deputy Mohamed Hamdan Daqlu (Hamideti), at a time when they were not yet at loggerheads. But there is no sign yet that they were able to salvage the deal.

THE TURKISH ROLE IN ETHIOPIA’S TIGRAY WAR AND THE DAM EQUATION

Another place where the use of Turkish weapons in internal conflicts has put Türkiye in a difficult situation is Ethiopia. TB2 drones sold to Ethiopia were used in the war against the Tigray region, according to Tigray fighters and some military experts from Dutch nongovernmental organization PAX and Amnesty International. This earned Türkiye the enmity of a part of Ethiopia. In 2020, there were reports that the course of the war between government forces and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front changed with the TB2s. Türkiye was forced to evacuate its embassy in Addis Ababa and move its consular services to Kenya for a while in case of a possible attack.

To strengthen its hand in tensions with Egypt and Sudan over the construction of the Renaissance (Hedasi) Dam on the Blue Nile, Ethiopia has put more emphasis on relations with Türkiye .

During this process, it was revealed that Ankara provided Ethiopian diplomats with training on hydropolitics to strengthen their country’s position against Egypt.

But when relations with Egypt normalized after Saudi Arabia and the UAE, Türkiye rebalanced between Addis Ababa and Cairo. Erdoğan realized that he could not sacrifice Egypt for the future of his larger interests in the region, especially in Libya. Egypt also started to show interest in the TB2 drones to strengthen its hand in the power equation. Meanwhile, on January 1, 2024, Ethiopia signed a 50-year agreement with Somaliland for the allocation of a naval base. According to the agreement, Ethiopia, which has no access to the Red Sea, will be able to use Somaliland’s Berbera Port. Türkiye , which logically should not have forced itself to choose between Ethiopia and Somalia, has been quicker and clearer than expected in favour of Mogadishu. Türkiye , which has a consulate in Somaliland, confirmed its commitment to Somalia’s unity, sovereignty, and territorial integrity. As Türkiye’s recent agreement to protect Somalian territorial waters also came as a retaliation for the Ethiopia-Somaliland agreement, Ankara was drawn back into the controversy, and the question of whether Türkiye -Ethiopia relations will be affected by this agreement was put on the agenda.

ERDOĞAN’S LOVE FOR DRONES, COUPS AND MILITARIZATION OF RELATIONS

Another critical point in Erdoğan’s opening to Africa is weapons. Every time the President travels to the continent, he looks to increase the number of drone customers. Having signed military-security cooperation agreements with 25 countries in Africa, Türkiye has so far sold defence products to more than half of these countries. Drones have a special place in those sales, particularly the TB2s which are produced by Baykar, the family company of Selçuk Bayraktar, Erdoğan’s son-in-law.

Erdoğan’s sending then-Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu to Bamako immediately after the coup in Mali in 2020 was perceived as an “opportunistic” appearance, and it bore fruit the following year, when Erdoğan announced the good news of military cooperation with Mali’s new junta. Soon, TB2s also arrived in Mali.

After being criticized for “siding with the coup plotters” in Mali, Erdoğan was more reserved when coups were repeated in Burkina Faso and Niger, but he continued to count the blows suffered by the colonial powers, especially France, as profit. French President Emmanuel Macron commented on the rising anger against the French in these countries as follows: “There is a strategy directed by foreign powers, such as Russia or Türkiye , who are playing on post-colonial resentment. We must not be naive: Most of those who appear in the French-speaking media, who give a voice, who make videos, are paid by Russia or Türkiye .”

Despite this, Türkiye has shown to be keen to build upon its pre-coup relations with Niger, which gained momentum with the signing of 29 bilateral agreements and Niger’s purchase of TB2s and HÜRKUŞ combat aircraft.

HUGE AMBITIONS; COLOSSAL INCOMPATIBILITY

Turkish schools, Yunus Emre Institutes, TRT Africa’s broadcasts in English, French, Swahili, and Hausa, the increasing number of representative offices of the state media agency, Anadolu, and the mosques being built, strengthen Türkiye ’s cultural and information pillar of the new hegemony in Africa. This hegemony is being forged along with Russia, China and India in the vacuum being left by the continent’s former colonial powers who are increasingly rejected. While these instruments are not enough for a Francophonie-like transformation, they have not been developed as extensively by China and Russia, and give Türkiye a competitive advantage. Türkiye’s geographical proximity also strengthens its hand. However, Türkiye’s share in Africa’s trade is not proportional to the size of the networks it has developed. The trade volume, which was $5.4 billion in 2003, increased to $40.7 billion in 20 years. Despite the growth, it is still a modest share of Türkiye ’s $617 billion total foreign trade volume last year and it has

high investment vulnerability due to its domestic economic instability. At the same time, it is overshadowed by large-scale actors such as China, whose trade volume with Africa reached $282 billion in 2023.

Despite this, the US values the initiatives, especially those with a military dimension, of its Turkish ally, which serve Washington’s interests of balancing China’s influence in Africa. As part of the international force in Somalia in 1993-1995, Türkiye essentially shared the same defeat as the US and Ankara’s quicker recovery and return prepared the ground for Washington’s. Türkiye is at odds with France in Africa, but the road map it is following coincides with the geostrategic interests of the US-British axis. In 2019, Türkiye’s involvement in the conflict in Libya in favor of the forces in Tripoli also received the support of the US-British duo as a move to balance Russia. According to the Anglo-Saxon perspective, the possibility of Russia “threatening” NATO from the south was eliminated by the Turks in Libya.

In conclusion, Africa is one of the geographies where Erdoğan’s motivation to become an imperial or sub-imperial power manifests itself. But Türkiye’s over-zealousness in adding a military dimension to relations is inadvertently embroiling itself in problems in the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa, and North Africa. The militarization of relations may offer an irresistible temptation to compete with former colonialists like France, but it also poisons Türkiye’s relations with the continent.

When the plan for a base in Suakin was put into action in addition to the bases in Somalia and Qatar, the columnists close to the AKP government fueled the enthusiasm for conquest with claims that the defense of Türkiye’s borders started from the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean, and the Persian Gulf. They argued that a Turkish triangle had been formed in the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, and the Indian Ocean. Undoubtedly, these arguments describe a state of inadequate ambition; that is, there is a gap between the size of ambitions and the capacity to fulfill them. Moreover, Türkiye’s exaggeration of its position has fueled fears among the Arab countries of the region. Since the declaration of the Year of Africa, Erdoğan has acted with the understanding that “the caravan is organized on the road”. This leads to many mistakes.

In Türkiye , African studies in universities are lacking and Ankara has too few diplomats who know Africa and can give the right advice to the government.

Where this kind of institutionalization is lacking, Erdoğan fosters relations through personal friendships which sometimes develop outside the bounds of law and diplomatic practice. For example, when the son of his Somali counterpart was involved in a fatal accident in Istanbul, Erdoğan could help the suspect escape, flouting the Turkish legal system. Erdoğan-style politics gets quick results, but it does not promise stability and leads to distorted relationships and scandals. Moreover, personal ties lose their relevance in ordinary or extraordinary changes of power and expose Türkiye to vulnerabilities.